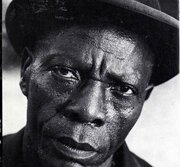

LE VISAGE DE L’ESCLAVAGE AFRICAIN EN IRAN (QAJAR) EN IMAGES — THE FACE OF AFRICAN SLAVERY IN QAJAR IRAN – IN PICTURES

LE VISAGE DE L’ESCLAVAGE AFRICAIN EN IRAN (QAJAR) EN IMAGES

THE FACE OF AFRICAN SLAVERY IN QAJAR IRAN IN PICTURES

PAR PEDRAM KHOSRONEJAD, ANTHROPOLOGUE, UNIVERSITÉ DE ST ANDREWS, ÉCOSSE

L’ANTROPOLOGUE PEDRAM KHOSRONEJAD A ENTREPRIS DE NOUVELLES RECHERCHES AU SUJET DE L’ESCLAVAGE DES AFRICAINS DANS LES ÉTUDES IRANIENNES – EN ÉLABORANT UN RÉCIT SUR L’ESCLAVAGE DES AFRICAINS EN PERSE À TRAVERS DES PHOTOGRAPHIES D’ARCHIVES, DES INTERVIEWS ET DES TEXTES DISPERSÉS. COMMISSAIRE DE L’EXPOSITION, SA COLLECTION EST EN PLEIN ÉSSOR

Anthropologist Pedram Khosronejad has embarked on a new and controversial topic in Iranian studies, developing a narrative on African slavery in Persia through archival photography, interviews and scattered text. Here he curates from his burgeoning collection

Qubad Il-khan Bakhtiari (à droite) et Hossein Il-khan Bakhtiari (à gauche), fils de chef suprême Bakhtiar Il-khan Khosrow Zafar Bakhtiari, assis dans un jardin , sans doute à Ispahan, avec leur esclave africain, 1904. Selon Khosronejad, cette photo montre que la propriété des esclaves en Perse prolongée au-delà de la monarchie Qajar aux chefs tribaux.

Qubad Il-khan Bakhtiari (right) and Hossein Il-khan Bakhtiari (left), sons of paramount Bakhtiar chief Il-khan Khosrow Zafar Bakhtiari, seated in a garden, probably in Isfahan, with their African slave, 1904. According to Khosronejad, this photo shows that slave ownership in Persia extended beyond the Qajar monarchy to tribal chiefs. Photograph : Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies, Tehran, Iran

La traite des esclaves africains dans le golfe Persique a commencé bien avant la période islamique. Des contes Médiévaux se réfèrent de façon sporadique à des esclaves qui travaillent comme domestiques, gardes du corps, des miliciens et des marins dans le golfe Persique, y compris dans ce qui est aujourd’hui le sud de l’Iran. La pratique a duré et a évolué à travers de nombreux siècles. Dans l’histoire moderne de l’Iran, les Africains faisaient partie intégrante des ménages d’élites. Les hommes noirs étaient pour la plupart des eunuques travaillant à l’intérieur du harem et les maisons du roi, tandis que les femmes noires étaient des servantes auprès des femmes iraniennes.

The African slave trade in the Persian Gulf began well before the Islamic period. Mediaeval accounts refer sporadically to slaves working as household servants, bodyguards, militiamen and sailors in the Persian Gulf including what is today southern Iran. The practice lasted, and evolved, through many centuries.

In Iran’s modern history, Africans were integral to elite households. Black men were mostly eunuchs working inside the king’s harem and houses, while black women were servants to Iranian women.

Les esclaves africains en Iran au cours de l’époque Qajar étaient souvent eunuques. Leur robe suggère qu’ils appartenaient aux membres roi ou de haut rang de sa cour. De droite : Aqay- i ’Almas khan, Aqay-i Bahram khan, Aqay-i Masrur, Aqay-i A Seyid Mustafa , Aqay-i Iqbal khan, et Aqay-i Yaqut khan, 1880. Photo : Fondation Kimia

African slaves in Iran during the Qajar era were often eunuchs. Their dress suggests that they belonged to the king or high-ranking members of his court. From right : Aqay-i ‘Almas khan, Aqay-i Bahram khan, Aqay-i Masrur, Aqay-i A Seyid Mustafa, Aqay-i Iqbal khan, and Aqay-i Yaqut khan (different person from other photo), 1880s Photograph : Kimia Foundation

En dépit de ses racines anciennes, le thème de l’esclavage africain est rarement discuté ou même reconnu en Iran. Ceci est en partie du au fait qu’il n’y a pas eu des recherches approfondies sur l’esclavage africain et l’utilisation ultérieure des domestiques africains.

Mais il y a des photos qui offrent des aperçus, et celles-ci ont fait l’objet d’analyses dans les travaux de recherche de l’anthropologue Pedram Khosronejad ses quatre dernières années.

Despite its ancient roots, the topic of African slavery is rarely discussed or even acknowledged in Iran. This is partly because there has not been comprehensive research on either African slavery of the subsequent use of African domestic servants.

But there are photographs that offer glimpses, and these have been the focus of anthropologist Pedram Khosronejad for the past four years.

Les esclaves qui ne sont pas des eunuques étaient parfois affectés aux armées d’élites Qajar. Les 14 photographiés ici appartenaient au prince Zell-e-Sultan de Qajar, Ghameshlou, Isfahan, 1904. Photo : Zell-e-Soltan / Fondation Kimia

Slaves who were not eunuchs were sometimes assigned to the armies of the Qajar elites. The 14 pictured here belonged to Qajar prince Zell-e-Soltan, Ghameshlou, Isfahan, 1904. Photograph : Zell-e-Soltan/Kimia Foundation

Khosronejad a récemment été nommé membre de Farzaneh Scholar pour les études iraniennes du Golfe Persique et, a un nouveau programme à l’Oklahoma State University. Le thème de l’esclavage africain en Iran est devenu sa préoccupation à la fin des années 1990, alors qu’il travaillait sur un projet ethnographique de deux ans dans le golfe Persique, y compris dans les villes de Minab, Bandar Lengeh et du comté dans la province de Bashagard Hormozegan. Ses études sur l’habit traditionnel des Iraniens noirs l’ont conduite à la question de l’esclavage.

Khosronejad was recently appointed Farzaneh Family Scholar for Iranian and Persian Gulf Studies, a new programme at the Oklahoma State University. The topic of African slavery in Iran came to his attention in the late 1990s when he was working on a two-year ethnographic project in the Persian Gulf including the cities of Minab, Bandar Lengeh and Bashagard county in Hormozegan province. His studies of the traditional dress of black Iranians led him to the issue of slavery.

Sur cette photo mise en scène prise par Zell-e Sultan à son palais de chasse d’été près d’Ispahan, l’un de ses esclaves africains tient son fils. Selon la légende, l’enfant (Iqbal) est le vrai fils de l’esclave africain adulte, Haji Yaqut Khan, suggérant qu’il n’était pas eunuque et donc pourrait être père de ses propres enfants. La légende dit que Yaqut Khan est dans ses vêtements ethniques (de languteh), qui ont été principalement portés par les Africains en dehors de l’Iran, 1904. Photo : Zell-e-Sultan / Fondation Kimia

In this staged photo taken by Zell-e Soltan at his summer hunting palace near Isfahan, one of his African slaves holds his son. According to the caption, the infant (Iqbal) is the real son of the adult African slave, Haji Yaqut Khan, suggesting he wasn’t a eunuch and could father his own children. The caption says that Yaqut Khan is in his ethnic clothes (languteh), which was mainly worn by Africans outside of Iran, 1904. Photograph : Zell-e-Soltan/Kimia Foundation

Kamran Afshar dans les bras de sa nourrice, Naneh Sonbol Baji, et Haleh Afshar, debout derrière une poupée, à Téhéran, 1940. Sonbol Baji, qui était d’origine africaine, est née dans un harem et libéré dans l’enfance de la cour du dernier roi Qajar, Ahmad Shah (1898-1930). Elle a déménagé à la maison de sa future famille d’accueil, les Afshars, où elle a grandi, marié et a élevé son fils. Elle y resta jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Photo : Gracieuse de Kamran Afshar

Kamran Afshar in the arms of his nanny, Naneh Sonbol Baji, and Haleh Afshar, standing behind a doll, in Tehran, 1940s. Sonbol Baji, who was of African extraction, was born in a harem and freed in childhood from the court of the last Qajar king, Ahmad Shah (1898-1930). She moved to the home of her future host family, the Afshars, where she grew up, married, and raised her son. She remained there until the end of her life. Photograph : Courtesy of Kamran Afshar

Plus tard, en 2011, lorsque Khosronejad organise un événement sur la photographie et la cinématographie sur Qajar à l’Université de St Andrews, en Ecosse, il ramène plusieurs photographies de la fin du 19ème siècle des Africains vivant à l’intérieur du harem du monarque Nasser al-Din Shah (1831 à 1896).

Later, in 2011, when Khosronejad was organising an event on Qajar photography and cinematography at the University of St Andrews, Scotland, he came across several photographs from the late 19th century of Africans living inside the harem of the monarch Nasser al-Din Shah (1831-1896).

Depuis Khosronejad a recueilli des photos qui racontent l’histoire des esclaves et domestiques africains modernes en Iran. Il a mené ses recherches en Iran, Espagne, au Royaume-Uni et aux États-Unis ; et il a passé au crible plusieurs archives privées dont celles de la collection personnelle de l’auteur Farhad Diba en Espagne et les Archives sur les débats modernes de Holland Park, Londres. Il a mené des dizaines d’entretiens avec les Iraniens, y compris avec Haleh Afshar, la baronne britannique d’origine iranienne qui avait des fonctionnaires africains au début des années 1950 et 1960.

Since then Khosronejad has been collecting photos that tell the story of African slaves and modern African domestics in Iran. His research has taken him to Iran, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, and he has sifted through several private archives including the personal collection of author Farhad Diba in Spain and the Archive of Modern Conflict in Holland Park, London. He has conducted dozens of interviews with Iranians including Haleh Afshar, the Iranian-born British baroness, who had African servants during the early 1950s and 1960s.

Shams al-Sho’ara (Abdulhossein Mirza Shams Molkara), assis, son beau-fils Amanullah Mirza Jahanbani (1869-1912) debout sur la droite, un petit garçon portant un chapeau (Mansour Mirza Jahanbani), autre garçon Azizollah, deux petites filles (Pouran Khanom Jahanbani, Touran Khanom Jahanbani), et une jeune esclave africaine, 1900s. Photo : Fondation Kimia

Shams al-Sho’ara (Abdulhossein Mirza Shams Molkara), seated, his son-in-law Amanullah Mirza Jahanbani (1869-1912) standing on the right, small boy wearing a hat (Mansour Mirza Jahanbani), other boy Azizollah, two little girls (Pouran Khanom Jahanbani, Touran Khanom Jahanbani), and an African slave girl, 1900s. Photograph : Kimia Foundation

Jusqu’à présent Khosronejad a recueilli environ 400 photos qu’il envisage de rassembler dans son premier ouvrage d’analyse visuelle sur les domestiques africains en Iran. Il prépare également plusieurs expositions connexes à travers le monde.

So far Khosronejad has collected around 400 photos, which he is planning to gather in the first-of-its-kind visual analysis book on African domestic servants in Iran. He is also preparing several related exhibitions around the world.

Ce travail est sensible. "Il y a quelques familles Qajar qui ont des problèmes avec le terme « esclave »’’, explique Khosronejad. "Ils disent ce que leurs familles avaient été domestiques et ils n’étaient pas traités comme des esclaves. Cela pourrait être vrai, mais l’esclavage est l’esclavage et nous devrions être en mesure de parler ouvertement. "

The work is sensitive. “There are some Qajar families who have issues with the term ‘slave’,” Khosronejad explains. “They say what their families had were domestic servants and they were not treated as slaves. This might be correct, but slavery is slavery and we should be able to talk about it openly.”

Sur cette photo prise et sous-titrée par le roi himelf, un groupe de femmes et des eunuques photographiés dans le jardin de harem l’un des complexes royaux au nord de Téhéran, Shahrestanak. Les cinq esclaves africains comprennent deux adultes, probablement éthiopiens, et trois adolescents : Haji Bilal (le premier esclave africain adulte à partir de la droite), Maqrur Khan (le quatrième adulte esclave africain à la droite), Ismail Khan (le premier esclave blanc adolescent de droite), Haji Rahim (le deuxième esclave blanc à droite, à la tête des esclaves du harem), 1883. Photo : Nasser al-Din Shah Archive/photo, Golestan Palace Museum, Téhéran, Iran.

In this photo taken and captioned by the king himelf, a group of his wives and eunuchs are shown inside the harem garden in one of the royal complexes in north Tehran, Shahrestanak. The five African slaves include two adults, probably Ethiopian, and three adolescents : Haji Bilal (the first adult African slave from the right), Maqrur Khan (the fourth adult African slave from the right), Ismail Khan (the first adolescent white slave from the right), Haji Rahim (the second white slave from the right, head of the harem slaves), 1883. Photograph : Nasser al-Din Shah/Photo Archive, Golestan Palace Museum, Tehran, Iran

La présentation de ces photos est la première étape vers ce que Khosronejad considère comme une nouvelle méthodologie dans l’anthropologie visuelle de l’Iran moderne : « Nous avons beaucoup de documents visuels qui ont une valeur de recherche. Certains d’entre eux ont été analysés par des artistes visuels ou des historiens, mais pas par des anthropologues. Nous avons besoin de lire ces photos comme des textes et des données à des fins anthropologiques ».

The presentation of these photos is the first step toward what Khosronejad sees as a new methodology in the visual anthropology of modern Iran : “We have lots of visual materials that have research value. Some of them have been analysed by visual artists or historians but not anthropologists. We need to read these photos as texts and data for anthropological purposes.”

Dans le cadre de ses responsabilités à l’Université Oklahoma State, Khosronejad et son équipe mettent au point une méthodologie d’évaluation des photos et des films documentaires d’un point de vue anthropologique. " Ces documents visuels portent des informations qui ne peuvent être trouvés dans les textes, "dit-il." Les analyses de ces anthropologues peuvent aider à faire progresser leurs études sur l’Iran. "

As part of his responsibilities at Oklahoma State University, Khosronejad and his team are developing a methodology for assessing photos and documentary films from an anthropological standpoint. “These visual materials bear information that cannot be found in texts,” he says. “Analysing them can help anthropologists advance their studies on Iran.”

Cette photo a probablement été prise par Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan (de 1850 à 1918), gouverneur d’Ispahan (1872 à 1907), et le fils aîné de Nasser al-Din Shah. Le fils de Zell-e-Soltan Bahram Mirza se trouve au milieu sur une chaise, accompagné de deux membres de sa cour (Reza Qoli Khan, secrétaire privé dans le droit et le chef eunuque Aqabaji dans la gauche) assis sur la droite et huit eunuques africains. La conception de la veste et le chapeau des esclaves africains pourrait être considéré comme un type de ségrégation ethnique. Photo : Farhad et Firouzeh Diba collection de photographies Qajar.

This photo was probably taken by Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan (1850-1918), governor of Isfahan (1872-1907), and the eldest son of Nasser al-Din Shah. Zell-e-Soltan’s son Bahram Mirza sits in the middle on a chair accompanied by two members of his court (Reza Qoli Khan, private secretary in the right and Aqabaji eunuch chief in the left) sitting on the right and eight African eunuchs. The design of the jacket and hat of the Africans slaves could be considered a type of ethnic segregation. Photograph : Farhad and Firouzeh Diba Collection of Qajar Photographs

Basé sur la légende écrite par Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan, le photographe de cette image était son esclave en chef, Aqabaji. Dans cette image quatre des esclaves africains adultes de Zell-e-Soltan sont vus en gardant un œil sur ses enfants, Chehel Sotun Palace, Isfahan. 1890. Photo : Aqa Suleyman Aqabaji / Fondation Kimia

Based on the caption written by Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan, the photographer of this image was his chief slave, Aqabaji. In this picture four of Zell-e-Soltan’s adult African slaves are seen keeping an eye on his children, Chehel Sotun Palace, Isfahan. 1890s Photograph : Aqa Suleyman Aqabaji/Kimia Foundation

Gholam Hoseyn Mirza Masoud, un des fils de Zell-e-Soltan, avec son esclave personnel africain, Julfa, Isfahan, 1880. Photo : Thooni Johannes/Institut d’études historiques iraniens contemporains, Téhéran, Iran.

Gholam Hoseyn Mirza Masoud, one of Zell-e-Soltan’s sons, with his personal African slave, Julfa, Isfahan, 1880s Photograph : Thooni Johannes/Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies, Tehran, Iran

Sur la base des sous-titres d’autres photos du même album écrit par Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan, le photographe de cette image est Zell-e-Soltan lui-même et le bébé dans l’image d’une petite-fille, probablement Nim Taj Khanum (Lady Nim Taj), avec son esclave africain, à Ispahan, 1890s. Au cours de la période de garde d’enfants Qajar et les enfants royaux et aristocratiques, l’accompagnement à leurs classes ont été parmi les principales fonctions des esclaves africains. Photo : Zell-e-Soltan/Fondation Kimia

Based on the captions of other photos from the same album written by Masoud Mirza Zell-e-Soltan, the photographer of this image is Zell-e-Soltan himself and the baby in the picture a granddaughter, probably Nim Taj Khanum (Lady Nim Taj), with her African slave, in Isfahan, 1890s. During the Qajar period babysitting and accompanying royal and aristocratic children to their classes were among the main duties of African slaves. Photograph : Zell-e-Soltan/Kimia Foundation

Saeed est né dans les années 1930 d’une mère africaine dans la maison de Abolhassan Diba (4 Janvier 1894 - 16 Avril 1982), et envoyé en Europe par Diba pour être formé en tant que Maître d’hôtel. Quand il est rentré en Iran dans les années 1950, il a commencé à travailler à l’Hôtel Park. Il a quitté l’Iran avant la révolution iranienne de 1979 et depuis lors, ses allées et venues sont inconnues. On le voit ici lors d’une fête de mariage, Téhéran, 1954 Photo : Farhad et Firouzeh Diba collection de photographies Qajar.

Saeed was born in the 1930s to an African mother in the house of Abolhassan Diba (4 January 1894-16 April 1982), and sent to Europe by Diba to be trained as a chef. When he returned to Iran in the 1950s he began working at the Park Hotel. He left Iran before the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and since then his whereabouts are unknown. Pictured here during a wedding celebration, Tehran, 1954 Photograph : Farhad and Firouzeh Diba Collection of Qajar Photographs

Une jeune aristocrate posant à côté de son eunuque personnel africain. Photo : Photographe inconnu/Bibliothèque centrale de l’Université de Téhéran, Téhéran, Iran.

A young aristocrat posing next to her personal African eunuch. Photograph : Unknown photographer/Central Library, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Cette photo (1895) a été prise par l’un des photographes les plus importants de l’époque Qajar, Abdullah Qajar (1850-1909). Dans cette photo rare, Nasser al-Din Shah est accompagné de ses fils, les membres de la cour, et la plupart de ses esclaves préférés et les plus influents. Il y a 10 eunuques africains sur la photo, parmi eux Haji Firouz (en blanc et debout derrière le roi) qui était l’un des esclaves les plus fiables du roi. Photo prise à l’extérieur de l’une des tentes royales, Norouz 1895 (Nouvel An iranien), peut-être Shahrestanak, Téhéran. Photo : Abdullah Qajar/Courtesy of Pedram Khosronejad/Fondation Kimia

This 1895 photo was taken by one of the most important photographers of the Qajar era, Abdullah Qajar (1850-1909). In this rare photo, Nasser al-Din Shah is accompanied by his sons, members of court, and most of his favourite and influential slaves. There are 10 African eunuchs in the photo, among them Haji Firouz (the one wearing white and standing behind the king) who was one of the most trusted slaves of the king. Outside one of the royal tents, Norouz 1895 (Iranian New Year), possibly Shahrestanak, Tehran. Photograph : Abdullah Qajar/Courtesy of Pedram Khosronejad/Kimia Foundation

Muzaffar al-Din Mirza (Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar 1853 - 1907) accompagné de son entourage. Débout à droite un esclave africain du prince Muzaffar Mirza ( Khajeh ), peut-être à Tabriz, Iran, 1880. Photo : photographe de la cour Inconnu/Bibliothèque centrale de l’Université de Téhéran, Téhéran, Iran

Muzaffar al-Din Mirza (Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar 1853-1907) accompanied by his entourage. Prince Muzaffar Mirza’s high-ranking African slave (khajeh) is standing on his right, possibly in Tabriz, Iran, 1880s. Photograph : Unknown court photographer/Central Library, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

Nasser al-Din Shah avait un intérêt particulier pour prendre des photos de ses propres esclaves à l’intérieur du harem. Sur cette photo, 53 esclaves eunuques d’origines ethniques différentes dans leur petite enfance, avaient probablement été récemment envoyé de l’étranger vers les marchés du sud locaux, et on voit le harem du roi. Parmi eux quatre garçons africains (qolam de bachehha), à l’intérieur du harem de Nasser al-Din Shah, Golestan Palace, Téhéran. Date inconnue. Photo : Bibliothèque centrale de l’Université de Téhéran, Téhéran, Iran

Nasser al-Din Shah had a special interest in taking photos of his own slaves inside the harem. In this photo, 53 eunuch slaves of different ethnic backgrounds in their early childhood, had probably been recently sent from abroad to the local southern markets, and to the king’s harem. Among them four African boys (qolam bachehha), inside Nasser al-Din Shah’s harem, Golestan Palace, Tehran. Date unknown. Photograph : Central Library, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran

© Le Bureau de Téhéran, une organisation indépendante d’information, organisée par le Guardian offrant des enquêtes originales, des commentaires et des analyses notamment comme c’est le cas ici sur l’une des histoires les plus importantes du monde.

Légende, Pedram Khosronejad.

contactus@tehranbureau

PEDRAM KHOSRONEJAD, ANTHROPOLOGUE, UNIVERSITÉ DE ST ANDREWS, ÉCOSSE

Pedram KHOSRONEJAD est chargé de recherche au Département d’Anthropologie Sociale de l’Université de St Andrews en Écosse. Il est aussi membre associé du Groupe Sociétés, Religions, Laïcités (EPHE-CNRS, Paris). C’est à l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS, Paris) que Pedram KHOSRONEJAD a obtenu son doctorat. Ses domaines de recherche incluent l’anthropologie sociale et culturelle, l’anthropologie de la mort, l’anthropologie visuelle, la piété visuelle, les objets de dévotion, ainsi que la culture matérielle religieuse. Pedram KHOSRONEJAD s’intéresse aussi tout particulièrement à l’Iran, aux mondes iranien, et au monde musulman.

Il a dirigé plusieurs ouvrages collectifs : The Art and Material Culture of Iranian Shi’ism : Iconography and Religious Devotion in Shi’i Islam (I.B.Tauris, 2011) ; Saints and their Pilgrims in Iran and Neighboring Countries (Sean Kingston, 2012) ; Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema : Religion, Martyrdom and National Identity (Sean Kingston, 2012) ; Unburied Memories : The Politics of Bodies, and the Material Culture of Sacred Defense Martyrs in Iran (Routledge, 2012). Il est également le rédacteur en chef de la revue Anthropology of the Contemporary Middle East and Central Eurasia (ACME).